The lobster is a magnificent creature.

As such, it has been captured not only in cooking pots and grills but also in pictures and art objects.

Still Life with Lobster, Drinking Horn and Glasses, 1653 Willem Kalf.

Oil on canvas

Dimensions 86.4 cm × 102.2 cm (34.0 in × 40.2 in)

National Gallery, London

‘In around 1653, the Dutch artist Willem Kalf painted a lobster. First he arranged it with various other delicacies and luxuries on a tabletop, ready to be carefully observed and copied on to canvas. The boiled crustacean was placed on a platter on top of a ruffled cloth, with a peeled lemon and a twinkling glass nearby. Over the tempting snack stands a spectacular buffalo drinking horn, embellished with silver.

Kalf’s painting is a monument to luxury. This is not a depiction of a proletarian meal. Vincent van Gogh’s much later work The Potato Eaters might be seen as a critical riposte to this and other 17th-century Dutch still lives of delicious feasts and snacks. While Vincent was trying to portray the lives of the desperate, Kalf entertained the well-off. The people who paid for paintings like his could surely also afford the actual lobster and the real drinking horn. (The drinking horn is believed to be associated with an Amsterdam archers’ guild, so perhaps this was commissioned for an officer in what was in effect an elite social club.)‘

Should art be austere in a recession? Jonathan Jones, The Guardian, 30 Jan 2012

Still Life with Lobsters, Eugene Delacroix, Date: 1826 – 1827

Style: Romanticism, Genre: still life

Media: oil, canvas

Dimensions: 80.5 x 106.5 cm

Musée du Louvre in Paris, France.

This artwork is in public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 70 years or less.

This painting comes from a group of artworks that Delacroix sent to the Salon of 1827.

The artist was asked to produce this painting specifically for General Coetlosquet.

On 28 September 1827, Delacroix wrote to his friend Charles-Raymond Soulier:

“I have finished the General’s animal picture, and I have dug up a rococo frame for it, which I have had regilded and which will do for it splendidly. It has already dazzled people at a gathering of amateurs, and I think it would be amusing to see it in the Salon.”

A. Joubin, Correspondance générale de Eugène Delacroix, Paris 1932–38, I, pp.196–97. After M. Hannoosh.

Delacroix is influenced by Constable in this picture, where he managed to put a landscape, something unusual for a still life.

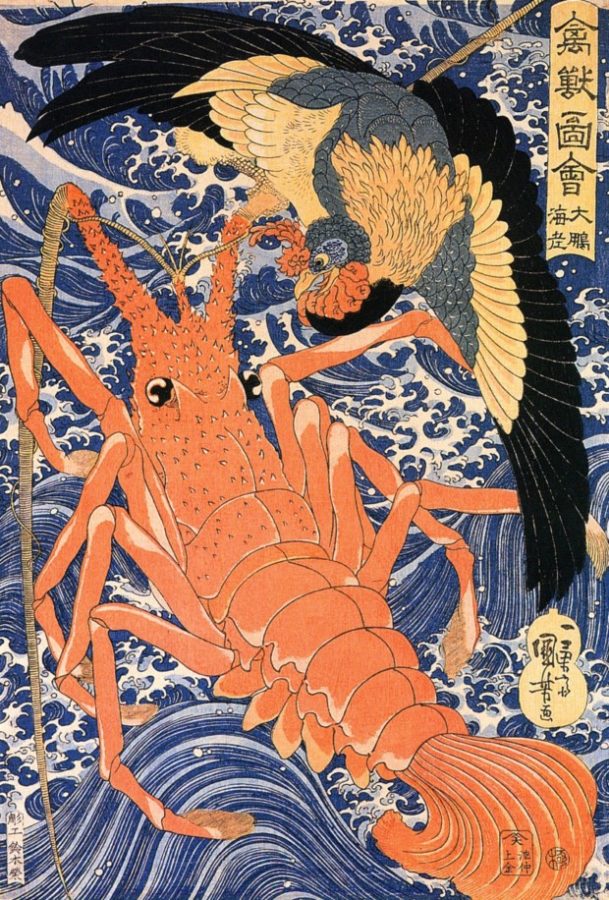

Phoenix and lobster, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1839-1841

Published by: Joshuya Kinzo

Woodblock print, oban tate-e.

Series: Series: Kinju zue (Birds and Beasts).

Dimensions: Height: 37.70 centimetres, Width: 25.40 centimetres.

British Museum, London

Lobster Telephone, 1938, Salvador Dalí

Tate Gallery, London

Lobster Telephone is an unexpected combination of objects. Dalí believed bringing them together could reveal secret desires. For him, both lobsters and telephones were connected with sex. This work is a classic example of a surrealist object. The surrealists promoted the idea that art could reflect the mysteries of the unconscious mind.

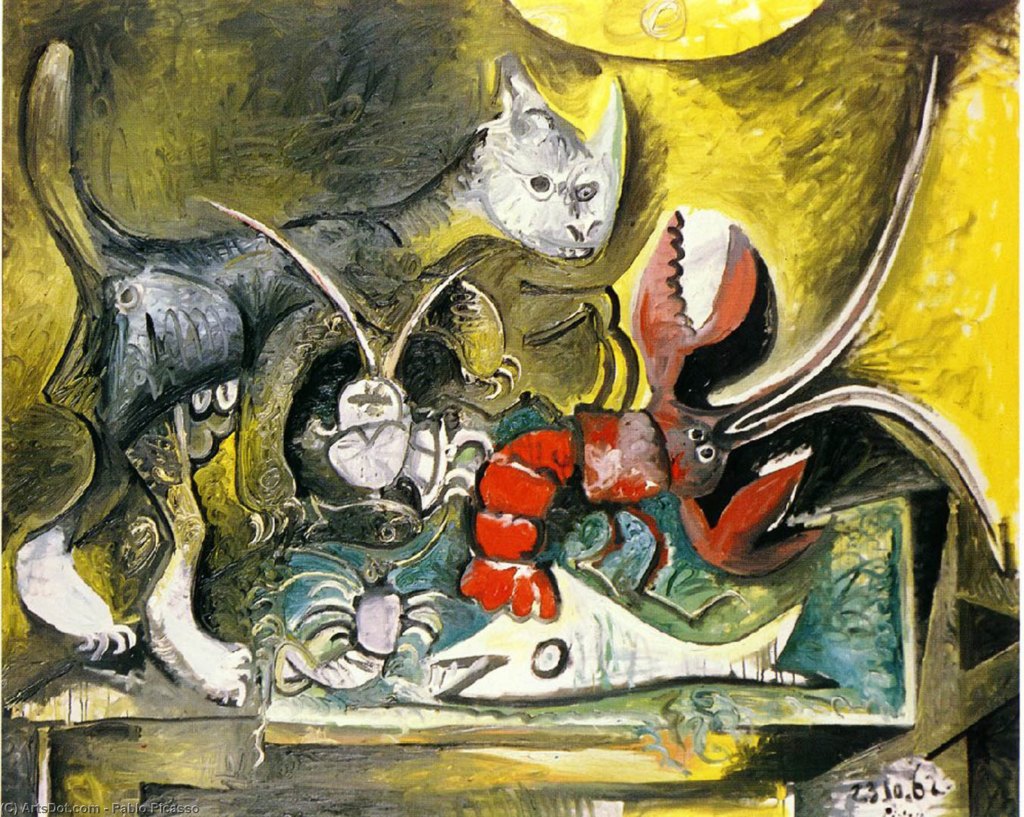

Pablo Picasso, Still life with cat and lobster, 1962, private collection.

The Still Life with Cat and Lobster copies the colours of Delacroix’s palette.

Lobster and Cat, Pablo Picasso, 1965

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 inches (73 x 92 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Thannhauser Collection, Bequest, Hilde Thannhauser, 1991

‘The latest of Pablo Picasso’s works in the Guggenheim’s Thannhauser Collection, Lobster and Cat attests to the artist’s unbroken creative energy during the last years of his life. The painting demonstrates Picasso’s ability to derive serious implications from what is essentially humorous. The subject of the lobster and cat refers to one of the most beloved paintings of French art, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s The Ray (1728, Musée du Louvre, Paris). In both paintings, a cat is aroused to vicious hissing by the menacing aspect of an item of seafood that is as delicious to the palate as it is horrendous to the eye.

What is so astonishing in Picasso’s painting is that he is able to retain the humorously anecdotal premise of the eighteenth-century genre painting while simultaneously heightening the encounter between cat and lobster into a miniature but extremely effective metaphor of aggression aroused by fear. It is a theme that preoccupied Picasso. If one makes all due allowances for the differences between the categories of miniature and monumental expression, it is a theme that also occurs in Picasso’s great mural Guernica (1937, Reina Sofía, Madrid). The comparison strikes an absurd note until one remembers Picasso’s frequent shifts from monumental to miniature, from trifling to significant and back again. These ostensibly erratic whimsicalities aim at an ironic demonstration of the artificial conventions of our thought and of our feelings. Here again, as in Lobster and Cat and in so much of Picasso’s work, it is impossible to think of Guernica’s bull or horse as being either all good or all evil, so is it impossible (on quite a different level of seriousness, of course) to come to a clear decision regarding the lobster and the cat in the Thannhauser painting. Both animals are potentially as innocent as they are dangerous.’

Jeff Koons, Lobster, 2003. Polychromed aluminium and coated steel chain

Dimensions: 57 7⁄8 x 37 x 17 1⁄8 in. (147 x 94 x 43.5 cm).

Collection of the artist. © Jeff Koons

The inflatable lobster, Lobster, 2003, speaks of an obvious and direct reference to Salvador Dalí. The banality of the work becomes surreal in its oversized context and playful appearance as an inflatable toy. Yet being made of aluminium and steel, the work deceives the perception of the viewer and carries a very real weight. Laden with associations to mechanical and large-scale productions it can be seen to reference consumerism on a mass scale, literally by means of the massive size of the lobster. It draws further associations to man’s intervention into nature: the creature has been mechanised and no longer possess the fragile ability of life but is now indestructible in its new found material form. Gathering no crowd like other more famous artworks, it goes to show the type of audience visiting the exhibition. Those only acquainted with Koons as a celebrity pass by the opportunities to see what else he has offered in his life works and the deeper contexts and meanings they hold.

Source: JEFF KOONS: A RETROSPECTIVE, WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK