This is a post of domestic dining table paintings and drawings.

Updated 20th August 2024.

The undeniable champion of this subject is the French painter Pierre Bonnard, followed by Edouard Vuillard. With their use of colours they expresses domesticity in a magnificent way, turning a daily activity into a small miracle.

Reconstruction of the Triclinium – a formal dining room – in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii by James Stanton-Abbott

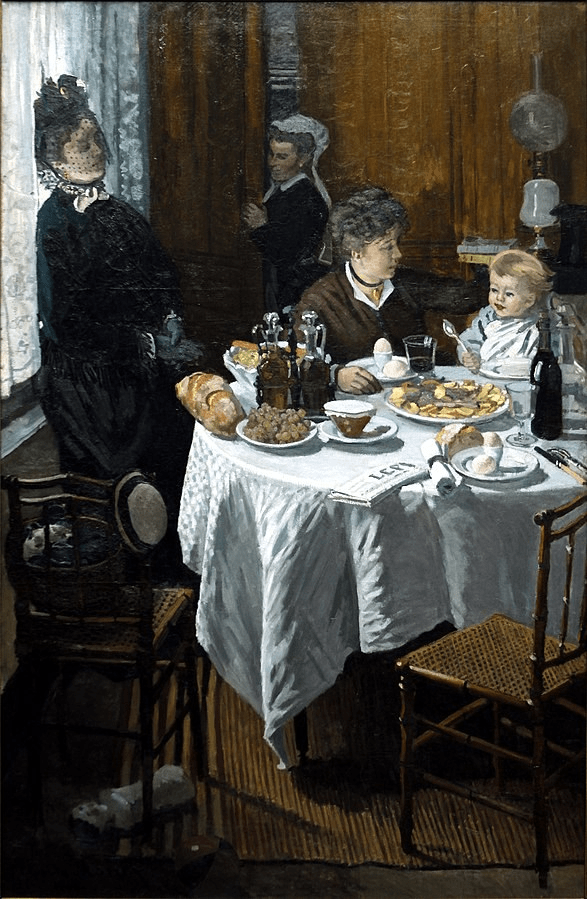

Claude Monet, ” The Luncheon ” 1868 – 1869

Oil on canvas 231.5 x 151.5 cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

This Claude Monet’s painting is autobiographical. As an artist constantly plagued by financial straits,Claude Monet had the fortune to receive a small “salary” from one of his patrons in the summer of 1868.For the 1st time,he was able to offer his family a proper home.It was his family who posed for him here,though Monet excluded himself from the depiction.

The jury of the conservative Paris Salon rejected the painting. It was not to be placed on public view until 1874, in the exhibitions independently organised by the Impressionists.

Berthe Morisot

In the Dining Room, c. 1875

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA

@ngadc

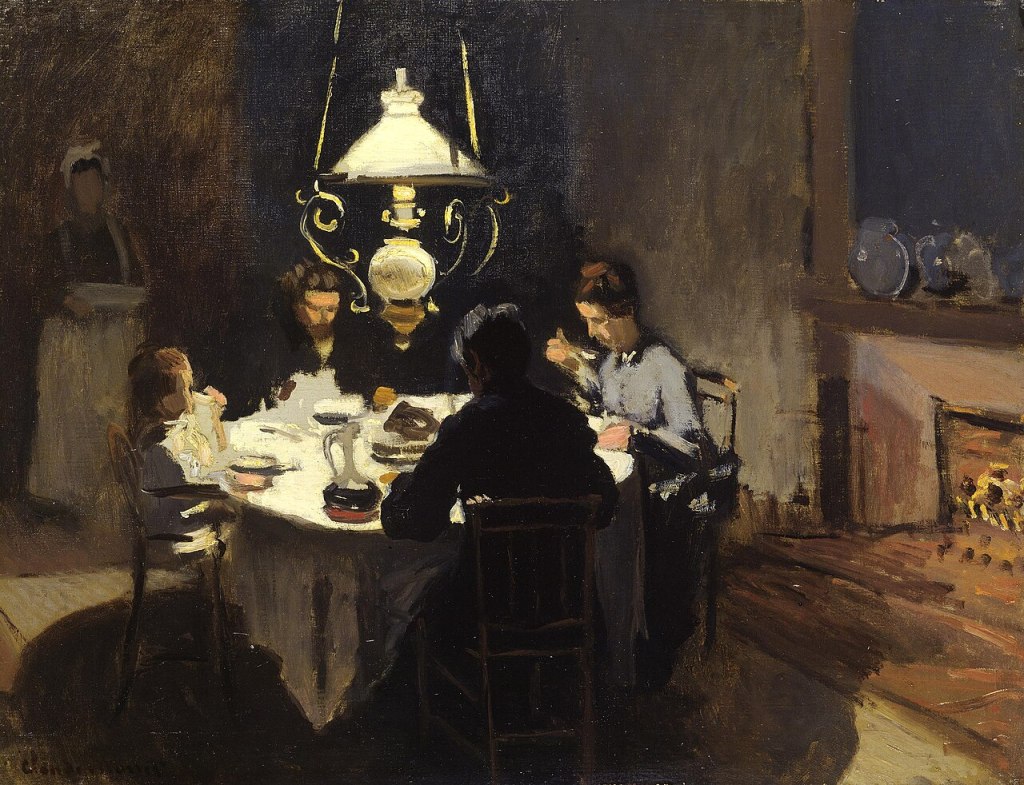

Claude Monet, The Dinner, 1868-69

Claude Monet, The Luncheon (Le Déjeuner: panneau décoratif), 1873

Huile sur toile

H. 160,0 ; L. 201,0 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France

After 1870, Monet gave up the large-scale paintings of his early days. However there were some exceptions: these are The Lunch exhibited in the second Impressionist exhibition of 1876 as a “decorative panel” and the paintings he produced in 1876-1877 for Ernest Hoschedé as decorations for the château de Rottenbourg in Montgeron. Possibly it was this Lunch, seen in Monet’s studio or at the 1876 exhibition, which prompted Hoschedé to commission the panels for his own estate.

The charm of the subject lies above all in the impression of spontaneity, in the simple evocation of a family life, some traces of which remain. The table has not been cleared at the end of a meal. A hat, hanging on the branch of a tree, a bag and a parasol left on the bench seem to have been forgotten there. In the cool shade of the green foliage, little Jean Monet quietly plays with a few pieces of wood.

As in other paintings, Monet here seems to come close to Vuillard and Bonnard who would treat these same subjects a few years later. The “close up” of the top half of the wicker tea trolley, contrasting with the female figure in the background on the right, also recalls certain techniques favoured by the Nabis.

Just imagine the delicious meals enjoyed in Claude Monet’s dining room at Giverny, France.

Claude Monet not only an Impressionist painter, but a true connoisseur who demanded that his asparagus be cooked just right (a little underdone), his salads be seasoned with a generous amount of pepper and his meals be served promptly on time. He was a generous host and welcomed many colleague artists to his table, among them Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley en Paul Cezanne.

A Dinner Table at Night, John Singer Sargent, 1884, Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 20 1/4 × 27 in. (51.4 × 68.6 cm)

Framed: 29 1/2 in. × 35 5/8 in. × 4 in. (74.9 × 90.5 × 10.2 cm)

Credit Line: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of the Atholl McBean Foundation

‘In 1884, Sargent visited Sussex to paint a full-length portrait of Edith Vickers (d. 1909). Among the many informal pictures he also produced during his sojourn in the countryside is this sketch of Edith and her husband, Albert (1839–1919), in their dining room. It is designed to appear without artifice, as if accidental rather than constructed. As the original title, The Glass of Port (Le Verre de Porto), implies, the work shows the moment after the dinner table has been cleared and decanters of port have been brought in.

The flowers, glass, and silver on the table are exquisitely rendered to reveal the reflection and absorption of the moody light in the room. Albert is only partially represented on the extreme margins of the canvas. Sargent’s use of reddish tones and the unorthodox disposition of the figures suggests the painting may have been inspired by the works of Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas.‘

John Singer Sargent ‘My Dining Room’

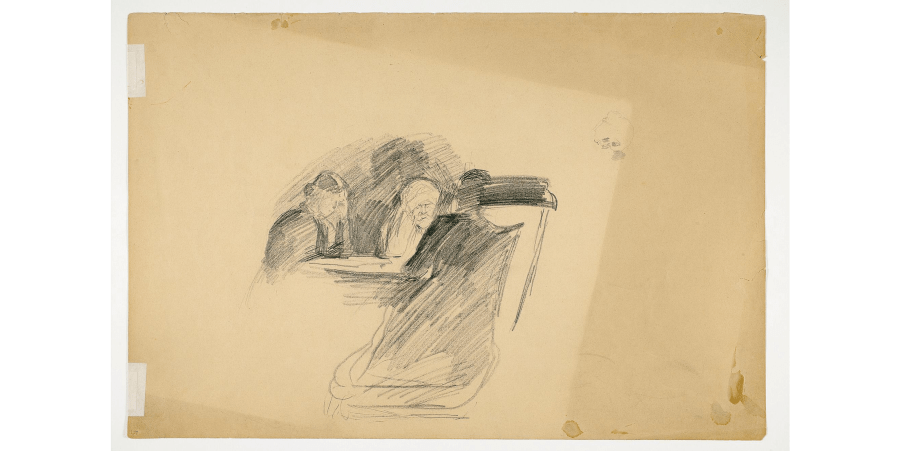

Around the Dinner Table, Edvard Munch, 1883–1885

Drawing, Pencil on Vellum paper

Dimensions: 480 × 317 × 0.2 mm

The Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway

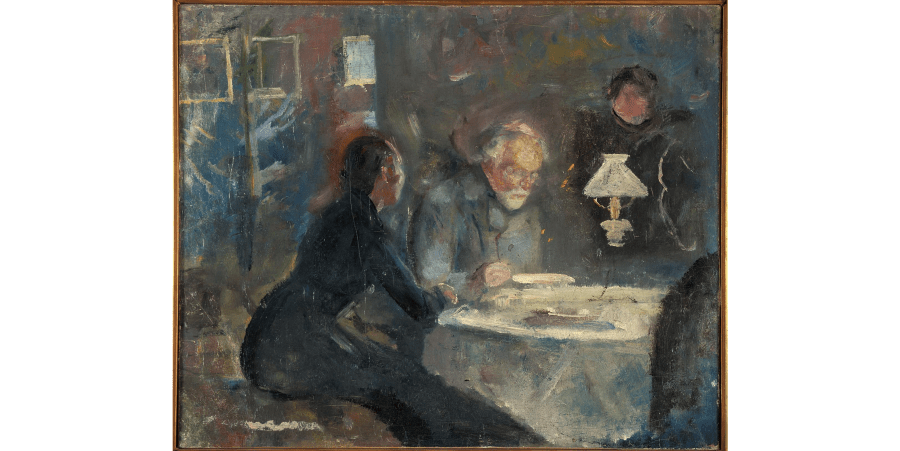

At Supper, Edvard Munch, 1883–1884, Oil on canvas

Technical dimensions: 48.9 × 59.6 cm

Framed: 53 x 63.7 x 4 cm

The Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway

Edouard Vuillard, The Luncheon, c.1895, 40 x 35 cm

Yale University Art Gallery

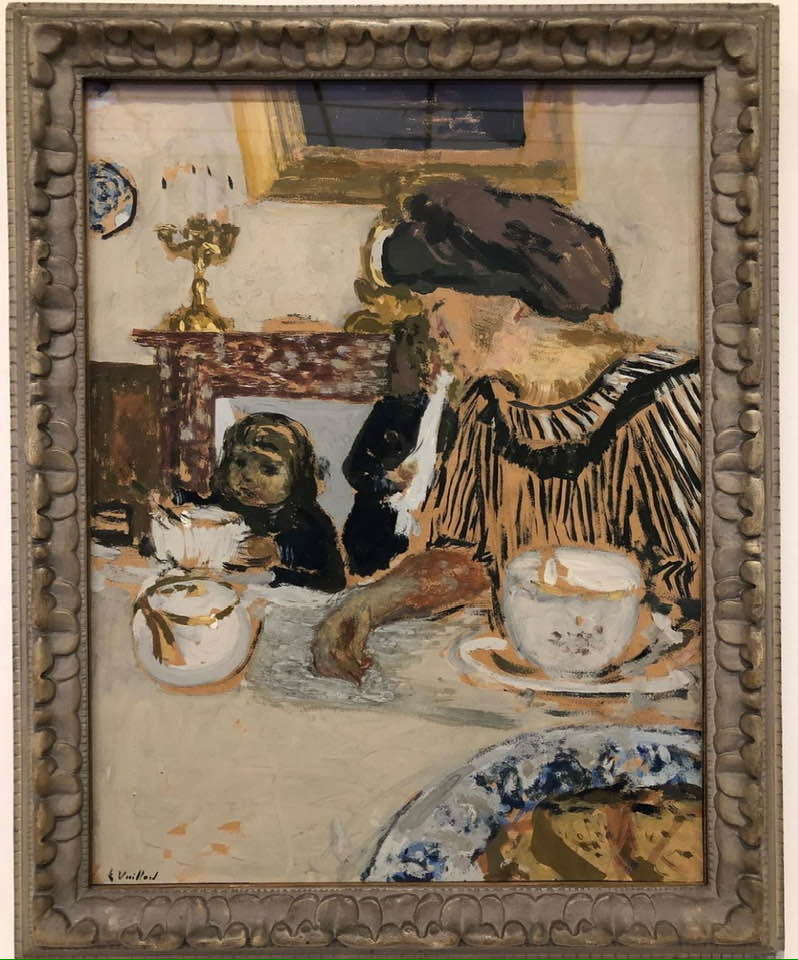

“Madame Vuillard à table”

stamped E. Vuillard (lower left)

oil on board 17⅞ by 19⅛ in. – 45.4 by 48.6 cm

Executed in 1896-97

Private Collection

Sothebys 15November 2023, 12:00 AM CET

New York – Lot 321

‘Madame Vuillard à table’ dates from the height of Vuillard’s Nabis period, when his pictures were at their most visually textured and saturated with color. It showcases Vuillard’s most studied subject, his mother, in his unique pictorial language. By 1890, Vuillard had begun collaborating with Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, and Paul Sérusier to establish the group known as “Les Nabis.”

Rejecting conventional perspective and academic subject matter, Vuillard and Les Nabis focused on the relationship between color and pattern on the flat surface of the canvas. The introduction to the Wildenstein exhibition of 1964 stresses the latter as a crucial component of Vuillard’s work:

“Through pattern Vuillard identifies his painted surface: the patterns formed by the objects take precedence over the objects themselves; shadow and substance are undifferentiated; natural and artificial things are fused” (Exh.Cat, New York, Wildenstein, Vuillard, 1964, p. 2-3).

https://www.sothebys.com/…/mode…/madame-vuillard-a-table

The Family Lunch (1898) – Édouard Vuillard

Oil on cardboard

64 x 42,5 cm

Private collection

(Salomon/Cogeval, Vol II: VII-036)

Pierre Bonnard, Le déjeuner (The luncheon),1899 oil/cardboard, (55 × 70 cm)

Foundation E.G. Bührle, Zürich, Switzerland

Pierre Bonnard, The Meal (At Table), 1899, oil on board (32 x 40 cm)

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK

Edouard Vuillard, The Dining Room in La Naz, 1900

Oil on cardboard mounted on panel

Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Édouard Vuillard, Das Speisezimmer, 1902

Hermitage

Edouard Vuillard,

Lunch, 1909,

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Copenhagen

John Singer SARGENT

Breakfast in the Loggia

1910

Freer Gallery of Art Collection, Washington D.C.

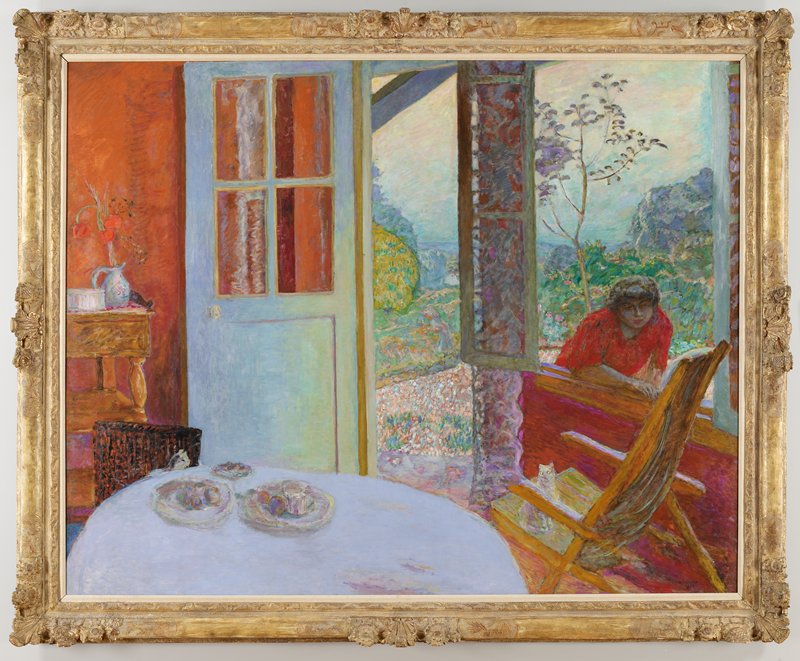

Dining Room in the Country, 1913, Pierre Bonnard

Dimension: 64 3/4 x 81 in. (164.47 x 205.74 cm) (canvas)

‘In 1912, Pierre Bonnard bought a country house called Ma Roulotte (“My Caravan”) at Vernonnet, a small town on the Seine. This painting shows the dining room there, with cats perching on the chairs and Marthe de Méligny, the artist’s wife, leaning on the windowsill. Bonnard, who considered himself “the last of the Impressionists,” emphasized the expressive qualities of bright colors and loose brushstrokes in this picture. He united the interior with the exterior through the open window and door, and linked the forms by bathing them in related hues. Unlike the Impressionists, however, Bonnard painted entirely from memory. And like the Symbolists, he wanted his works to reflect his subjective response to the subject.’

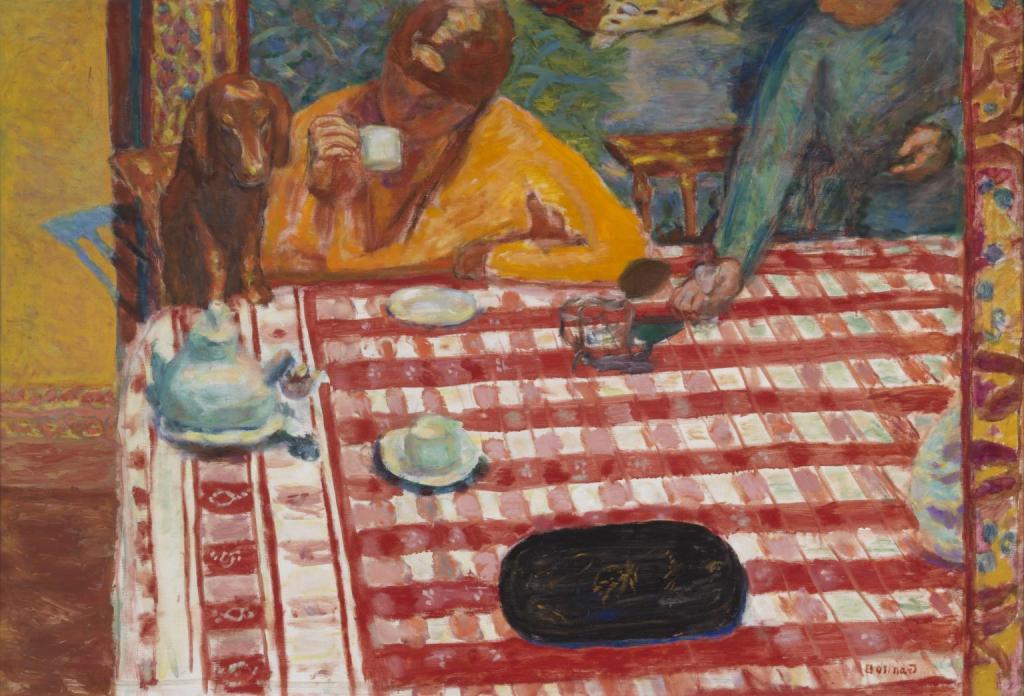

Coffee, 1915, Pierre Bonnard, Oil paint on canvas

DIMENSIONS support: 730 × 1064 mm frame: 948 × 1282 × 95 mm

Tate Gallery, London

‘The dining table was one of Bonnard’s favourite subjects. Its associations with domestic routine and conviviality were in tune with his intimate vision of art. Here, the artist’s wife Marthe sips coffee, with her pet dog at her side. The table stretches invitingly before us, so that the painting appears to record the casual glance of someone about to sit down opposite Marthe. As can be seen in the preparatory sketches shown alongside the painting here, Bonnard’s composition was carefully planned and developed.‘

‘Coffee 1915 (Tate N05414) is a large oil painting on canvas by the French artist Pierre Bonnard. Three pencil sketches on paper relating to the work, all entitled Preparatory Sketch for ‘Coffee’ and each made in 1915, are also in Tate’s collection (Tate T06545, T06546, T06547). In the painting, a table is shown from the front and at a slightly elevated angle. It is covered in a bright red and white checked tablecloth on which a coffee pot, two white cups and a serving platter for food have been placed. The table is only partially shown and extends into the foreground to meet the canvas’s lower edge. A woman dressed in vivid yellow sits at the far side of the table, sipping a cup of coffee and turning towards a small dog, who is standing on the edge of the chair with two paws on the table. The torso and arm of a second woman, dressed in blue, is seen reaching down towards a glass on the table, and it is unclear whether she is entering or leaving the room. The composition is framed at the right by a yellow, red and blue decorative border running down the side of the painting; this is echoed by a similar band of colour on the wall behind the dog. A wall hanging or painting appears in the background. The palette is restricted almost entirely to red, yellow, blue, white and brown, and the black serving platter contrasts strikingly with the vibrant tablecloth, providing a solid form on which to focus. Some objects, such as the chair to the left, cast strong shadows in vivid colours. The atmosphere is one of quiet domesticity and the viewer is positioned as if about to join the woman.

The three sketches, all executed rapidly, show elements of the composition in progress. T06547 is the least resolved, with a loose rendering of the heads and upper bodies of the dog and seated woman. T06546 depicts the seated woman sipping coffee, a coffee pot on the table and a decorative background, as well as the dog, which in this version is seated. T06545 concentrates on refining the movement of the central figure: she holds her coffee cup aloft, caught in the act of drinking; the tablecloth has appeared and the dog stands, front paws balancing on the table, on which most of the objects featured in the painting have been sketched.

Bonnard created these images in 1915, most likely a house he rented in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Paris. In the case of Coffee, which has also been known as Afternoon Tea, oil paint has been loosely and vigorously applied to the canvas and there is evidence of colours bleeding into each other, most notably the red and white of the tablecloth. Bonnard has selected intense pigments including vermilion, cadmium and strontium yellows, cadmium orange, cobalt blue, Prussian blue and natural ultramarine. The painting is signed in the lower right corner. There is evidence of alterations in the work, and art historian Timothy Hyman has noted that the composition has been significantly extended along the lower edge and that the chair on the right has been moved towards the centre, with the standing woman painted over it and extended (Timothy Hyman, Bonnard, London 1998, p.92). The sketches also provide evidence of Bonnard’s reworking, in particular the placement of the seated woman and the dog. Her position changes markedly from a relaxed intimacy with her pet in T06547, to sitting alongside it in T06546, to twisting towards it in T06545. The sketches are uniform in size and it is likely that they initially formed part of a sketchbook.

The subject of focus in the painting and sketches is Bonnard’s wife, Marthe. The artist’s domestic life was a major focus for his work. Art historian Nicholas Watkins has described how domestic settings allowed Bonnard to record the ‘atmosphere, incidents and relationships that caught his eye’ (Watkins 2002, p.56). A large part of the composition of Coffee, and that of sketches T06545 and T06546, is taken up by the table. The critic Richard Cork has emphasised the importance of Marthe’s positioning at the end of the table: ‘you get the very strong feeling the artist is sitting at the table himself. Although he looks down on the scene from a slightly aerial viewpoint, he’s very close to, almost as though he’s participating in the drinking or eating’ (Richard Cork, ‘Audio Transcript: Pierre Bonnard’s Coffee’, no date, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/bonnard-coffee-n05414/text-audio-transcript, accessed 20 May 2016). Cork has also suggested that in Coffee, which was painted during the First World War, Bonnard ‘hid himself away from what else was happening in the world and concentrated on everything that was around him’ (Cork, no date, accessed 20 May 2016). Watkins has stated that Bonnard’s ‘little drawings, quickly sketched in a pad secreted in his hand, assumed an extremely important function in his art; they represented his codified sensations of specific experiences and served as the starting point for paintings executed in the studio’ (Watkins 2002, p.134). Bonnard himself stated that for him ‘drawing is sensation. Colour is reasoning’, arguably a reversal of traditional definitions of these two elements of mark-making (quoted in Watkins 2002, p.134).

In 1944 Bonnard stated: ‘I float between intimism and decoration, one does not reformulate oneself’ (quoted in Watkins 2002, p.59). His interest in painting as decoration can be traced to the influence of his contemporary Henri Matisse as well as his early association with the post-impressionist movement Les Nabis, including his close associate Edouard Vuillard. This is also evident in the fleeting, transforming power of light captured in Coffee and its emphasis on colour as a means of defining form.

Jo Kear

May 2016‘

Pierre Bonnard, After dinner (Après le diner), circa 1920, Oil on Canvas (76 x 80 cm)

Cleveland Museum of Art, OH, US

In this painting Bonnard gives us a colorful glimpse of an intimate dinner scene at the beginning of the 20th century. He places us close to the figures and a little bit higher, as if we were just standing to leave the table, allowing the viewer to imagine being part of the scene.

This domestic scene depicts a woman at a dining table accompanied by a young man at whose side is a small dog, just visible at the edge of the table. The woman is the artist’s wife, Marthe. The boy has been identified as Ari Redon, the son of artist Odilon Redon; the dachshund is the Bonnard family pet, Poucette. The painting explores the simple pleasures of daily life—a shared meal, quiet companionship—enriched through the application of glowing, sensual color.

Pierre Bonnard The Dining Room, 1923. Israel Museum, Jerusalem, gift of Sam Spiegel.

One of the artist’s interiors, a frozen moment, yet multiple figures appear as if by time-lapse, and colours dissolve and melt together.

The Table, 1925, Pierre Bonnard, Oil paint on canvas

DIMENSIONS support: 1029 × 743 mm frame: 1256 × 965 × 113 mm

Tate Modern, London

‘The woman is probably Marthe Bonnard, the artist’s wife. She is looking towards a dog whose muzzle is faintly visible on the left, and seems to be preparing its food in a bowl.’

Jeune Femme à Table (1925) – Pierre Bonnard

oil on canvas

45.7 x 67.3 cm

Auctioned at Christie’s in 2016

This painting depicts Marthe de Méligny–Bonnard’s lifelong partner and muse–in the dining room of the house that they shared at Vernonnet. The year that he and Marthe finally married, in 1925, he painted her no fewer than ten times in the wood-paneled dining room, with its ornate fireplace and free-standing buffet.

Pierre Bonnard.

Le déjeuner, 1923. Oil on canvas.

In the National Gallery of Art, Dublin.

Pierre Bonnard, Dining Room on the Garden (Grande salle à manger sur le jardin), 1934 – 1935

Oil on canvas

50 x 53 1/4 in(127 x 135.3 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

‘At the time Bonnard was painting this summer breakfast scene, Rockefeller Center stood half built and Europe was gearing itself for war. Yet the modern world seems all but ignored in Bonnard’s painting, which harks back to the artistic tenets of the late 19th century, its vibrant colors conjuring up the canvases and theories of Paul Gauguin‘s circle. Around 1890, Bonnard belonged to the Nabis (from the Hebrew word for “prophet”), a group that tended to paint mystical or occult scenes in order to invoke extraordinary psychic states. As this painting shows, Bonnard still lent a hallucinatory aura to the everyday some 40 years later.

Bonnard resolutely painted subjects such as those in Dining Room on the Garden (Grande salle à manger sur le jardin, 1934–35) for most of his life, being called très japonard (very Japanese-like) for his attempts to create a charged psychological moment in a virtually non-perspectival domestic space reminiscent of Japanese prints. This painting, one of more than 60 dining-room scenes he made between 1927 and 1947, is neither decorative (as these works have often been called) nor is its subject truly his first concern. Dining Room on the Garden sets out to capture the moment and the intrinsically ungraspable play of mood and light. On close inspection, the colored areas within the flattened picture plane lose their relation to the objects depicted: a chair melds into the window frame; the window echoes the painting’s borders, becoming a view within a view; and Marthe, the painter’s oft-depicted wife, merges passively into her surroundings. It is in his ability to create a timeless microcosm while laying bare the gesture of applying paint to canvas that Bonnard’s modernism is revealed.’

Cornelia Lauf

David Hockney (britannique, né en 1937)

Tyler Dining Room from Moving Focus, 1985

Estampes et multiples, Lithograph in colors, on TGL handmade paper

32.12 x 40 in. (81,6 x 101,6 cm.)