Updated 20th August 2024.

This is a post of restaurant paintings and drawings, indoors and outdoors.

The American painter Edward Hopper dominates the subject. Not so much in volume, as in essence. His view is full of intensity, loneliness, anxiety, existential dead ends.

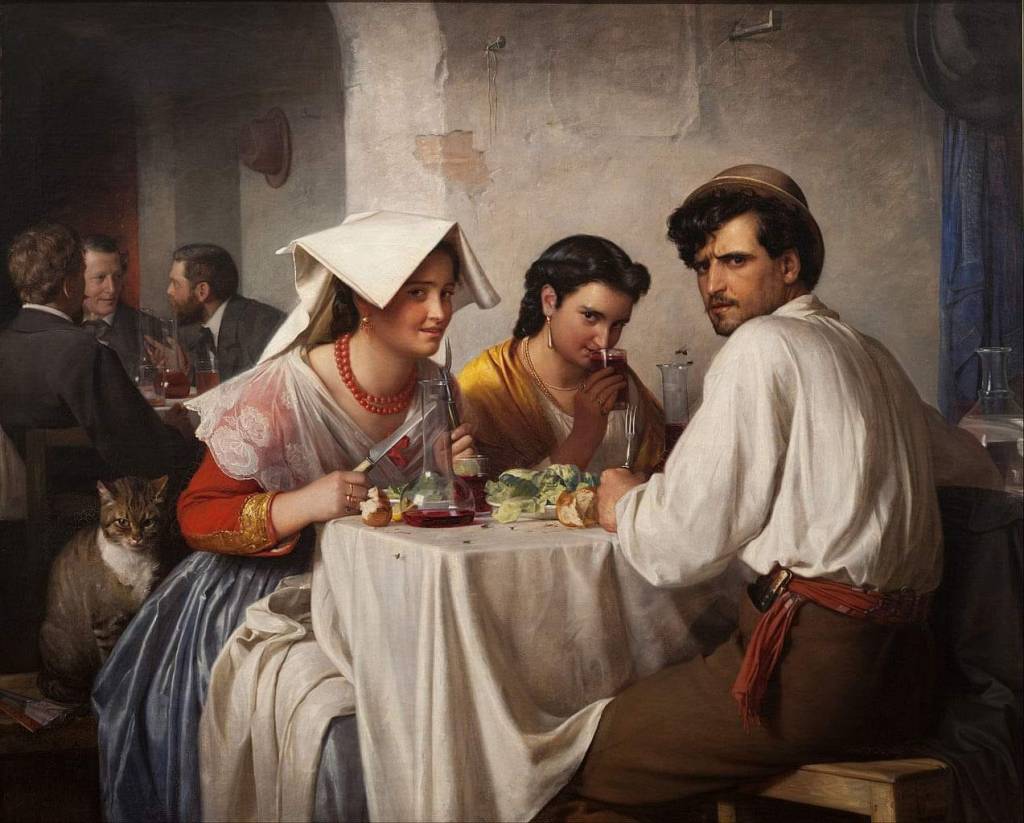

Carl Bloch (Danish, 1834–1890)

“In a Roman Osteria” (1866).

Oil on canvas,

148.5 × 177.5 cm (58.5 × 69.9 in).

National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen

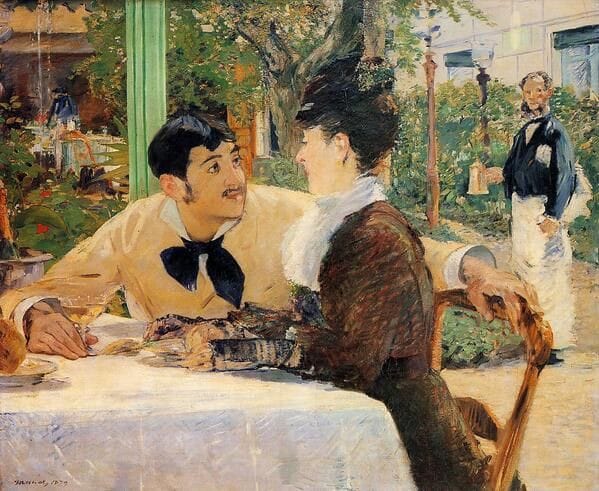

Édouard Manet

Chez le Père Lathuille, 1879

The picture was painted at the restaurant Pere Lathuille, an old establishment near the Clichy tollhouse. (Its sign appears in a picture by Horace Vernet.) In Manet’s day, the restaurant was near the Guerbois, off the avenue de Clichy. The model for the woman was Mile French, who took over from the original model, Ellen Andree, when she had to break off the sittings. The young dandy is the son of the proprietor, M. Gauthier-Lathuille. Tabarant knew him later when he had turned the old restaurant into a cafe-concert, the Eden. It was then that Gauthier-Lathuille told him the story of Manet’s painting. He had met Manet at his parents’ restaurant while he was a volunteer in a regiment of dragoons. He was to have posed in uniform with Ellen Andree, who was at that time still very young, charming, amusing, and beautifully dressed. After two sittings the picture was progressing very well, but at the third – no Ellen Andree. She begged to be excused: she was rehearsing a play. Two days later, she met with a rather cool reception from Manet, who said that if that was how things stood, he could do without her. “The next day,” recounted Gautluer-Lathuille, “I saw Manet come in with Mile Judith French, a relative of Offenbach. I took up my pose again with her, but it was not the same thing. Manet was fidgety. ‘Take off your jacket and put on mine,’ he said to me at last, handing me his own jacket of tussore silk. He then began to scrape the canvas, and thus it was decided that I should pose in civilian clothes with Mile French.”

Vincent Van Gogh, The Restaurant de la Sirène in Asnières, 1887, oil on canvas

H. 54,0 ; L. 65,5 cm.

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

‘During his stay in Paris, between March 1886 and February 1888, Van Gogh lived with his brother Theo in the north of the city: first in rue de Laval, then in rue Lepic from June 1886. Unlike other Impressionists who, in summer, were able to afford even a modest holiday in the country, Vincent, by choice as much as necessity, sought out locations near to where he lived. This was the case with Asnières, a town situated on the banks of the Seine, not far from the fortifications of Paris. There he painted and drew several views of bridges or, as here, of the restaurant de la Sirène.

Both style and subject had precedents in Impressionism, yet the painting moves away from them in some respects. It reflects the exterior appearance of the buildings more than the convivial pleasures enjoyed inside. The Impressionists, and above all Renoir, often depicted restaurants, but preferred to evoke the atmosphere inside them.

In The Restaurant de la Sirène Van Gogh increased the white brushstrokes, while still using the full richness of his palette. The painter Emile Bernard was without doubt alluding to a depiction of the restaurant de la Sirène when he recounted to Vuillard that some of the works Van Gogh produced in Paris featured “smart restaurants decorated with coloured awnings and oleanders”. Although this painting is one of his closest in style to Impressionism, Van Gogh increased the parallel hatching thus suggesting a more personal style that would soon reach its peak.‘

Vincent van Gogh, The Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887.

Medium Oil on canvas

Dimensions (Unframed) 28 7/8 x 23 5/8 in. (73.3 x 60.0 cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.10.

Photo courtesy Nelson-Atkins Media Services, Jamison Miller

Vincent van Gogh, Interior of a Restaurant, Summer 1887

Interior of a restaurant is one of Van Gogh’s most pointillist works. Although he applies the stippling technique in his own distinctive manner. The tables and chairs are not rendered in dots, but in long brushstrokes. Moreover, he uses gradations of colour to suggest shadows, a practice from realism that is not consistent with pointillism.

Exuberant bouquets adorn the tables laid with white tablecloths, like floral still lifes. High in the corner, a black hat ‘floats’ as a reference to a Parisian, who is about to take a seat at the table. The contrasts between the complementary colours – red and green for the walls, yellow and (grey) purple for the floor, and the yellow-orange of the furniture – with the blue in the tablecloths have been carefully applied.

Van Gogh may well have intended the work as a kind of homage to modern art. The poster or ‘crepon’ on the wall on the right indicates his interest in Japanese printmaking. The painting in the middle is his own, also pointillist work Lane in Voyer d’Argenson Park at Asnières. It is possible that he is alluding to the role that he himself hopes to play in the development of the new art.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1864 – 1901)

“Aux Ambassadeurs, Gens Chics” (Fashionable People at Les Ambassadeurs) 1893

Oil with essence over black chalk on wove paper, mounted on cardboard.

Washington, National Gallery of Art.

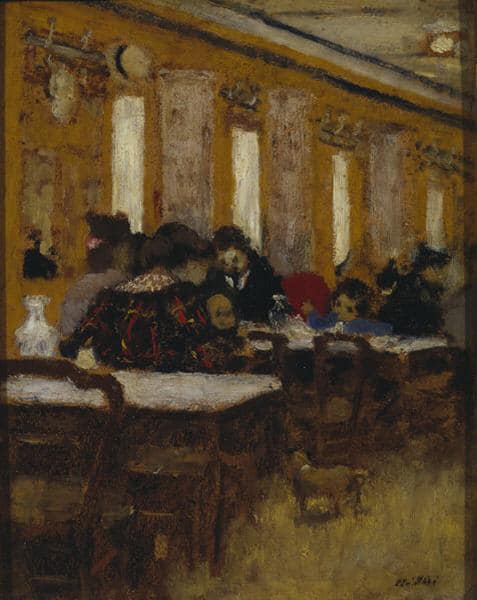

The Little Restaurant, Edouard Vuillard, 1894

Media: oil, panel

Location: Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX, US

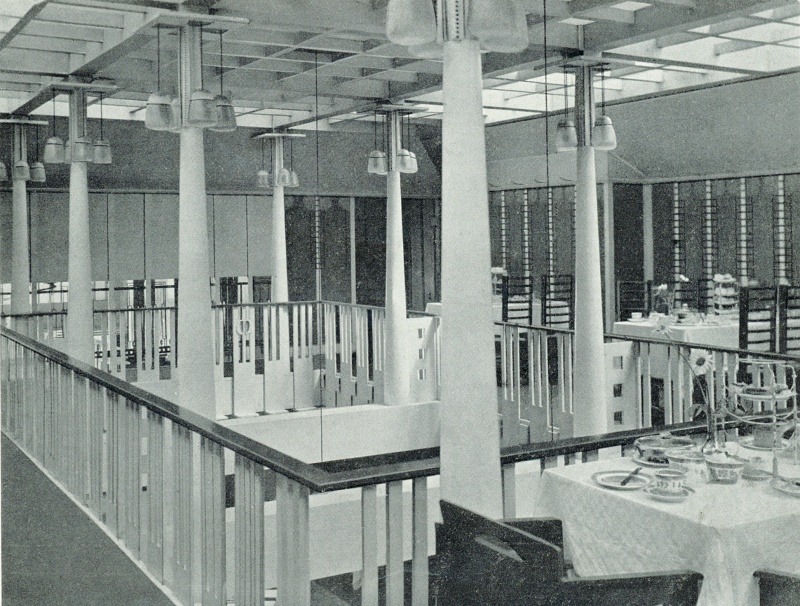

The opening of the Willow Tea Rooms in 1903 was met with resounding acclaim from the public and press alike, captivating the city with its revolutionary design. The Glasgow Evening News lauded the establishment as ‘the acme of originality’. Highlighted were the Salon de Luxe and the stairway, emblematic of the meticulous attention to detail and innovation. The Bailie echoed this sentiment, hailing the tea rooms as unparalleled in arrangement and colour, while the Glasgow Advertiser & Property Circular praised the craftsmanship of the contractors and the artistic scheme executed with precision.

Glasgow journalist Neil Munro, through his character Erchie, captured the public’s fascination with the Willow Tea Rooms in a humorous narrative, showcasing admiration for the exquisite decor and Miss Cranston’s acumen for choosing such novel design.

However, the architectural press remained relatively silent until the German journal Dekorative Kunst published a comprehensive article in 1905. Author, Fernando Agnoletti, a fervent supporter of Mackintosh, declared the tea rooms as a ‘fairyland’ conjured by a ‘sorcerer’. Agnoletti celebrated Mackintosh’s mastery in achieving unity of effect and simplicity, transforming the Willow Tea Rooms into an oasis of beauty amidst the city’s hustle.

Such press coverage solidified Mackintosh’s status as a visionary architect, paving the way for fuller recognition of his work in his homeland.

Visit the iconic original Willow Tea Rooms building: https://www.mackintoshatthewillow.com/book-now-2/

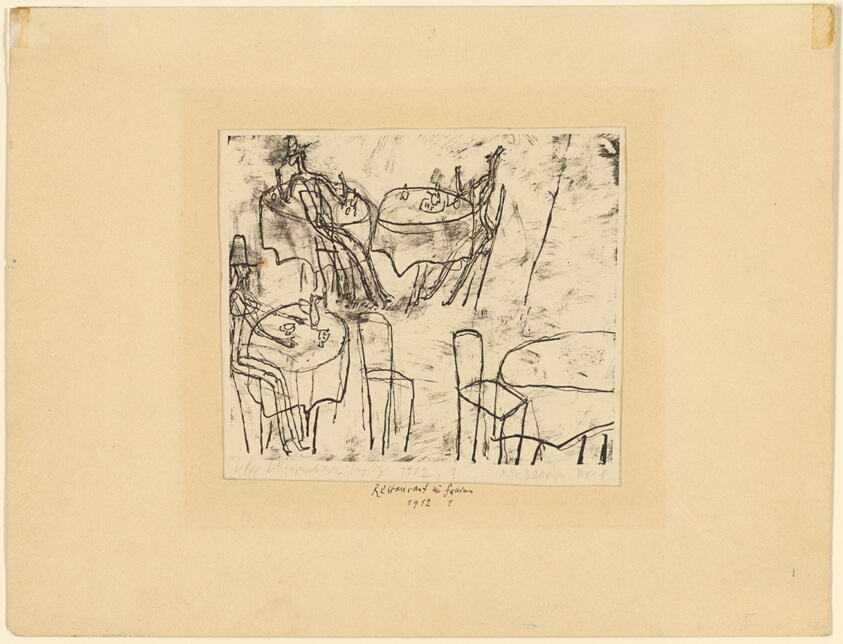

Paul Klee, Outdoor Restaurant, 1912

Dimensions

View, sheet: 12.8 × 14 cm (5 1/16 × 5 9/16 in.); Support: 22.4 × 29.3 cm (8 7/8 × 11 9/16 in.)

Art Institute of Chicago

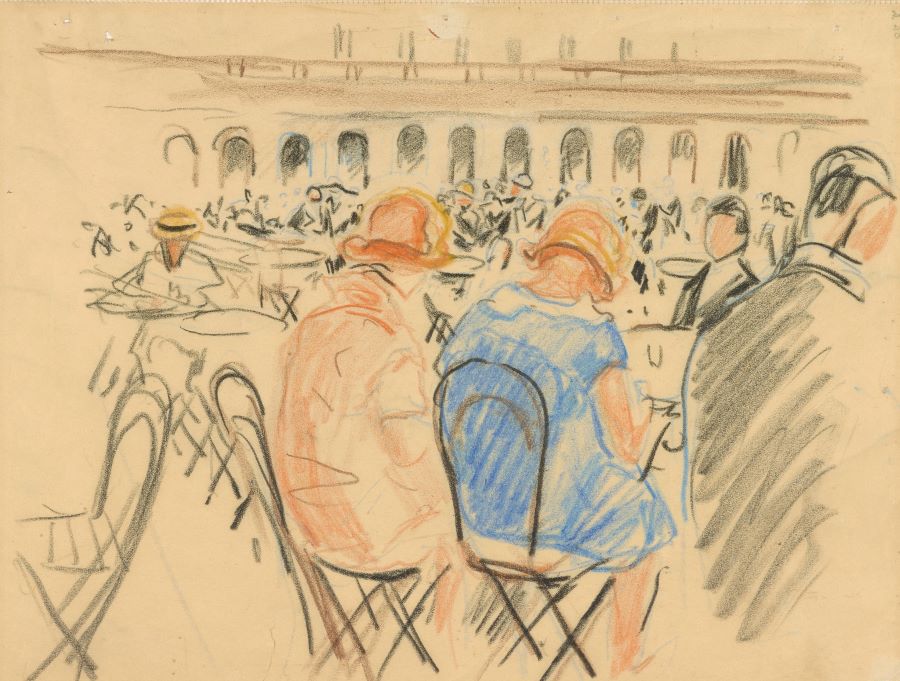

When I compare Klee and Munch (see below), I cannot help but notice that Klee is much bolder, daring, adventurous.

Klee’s drawing is modern, intense, abstract.

Munch’s drawing in contrast seems to be conservative.

It is important to notice that Klee drew his work 12 years earlier than Munch.

Two Signal Corps staff eating dinner. 136 Rue Jean Jaures. World War I. Brest, France in 1919.

Bibi (Madeleine Messager) at the New Eden Roc Restaurant. Cap d’Antibes. 1920

Photo by Jacques-Henri Lartigue (June 13, 1894 – September 12, 1986) a French photographer and painter, known for his photographs of automobile races, planes and Parisian fashion female models

New York Restaurant, Edward Hopper, circa 1922, oil on canvas

Dimensions height: 61 cm (24 in); width: 76.2 cm (30 in)

Collection: Muskegon Museum of Art

‘A first look at Hopper’s work reveals the important role that light plays in evoking the atmosphere characteristic of his paintings. Natural and artificial light create a borderland of either clarity or oppressive density. Some of Hopper’s paintings from the twenties show how his depiction of light defines the human situation.

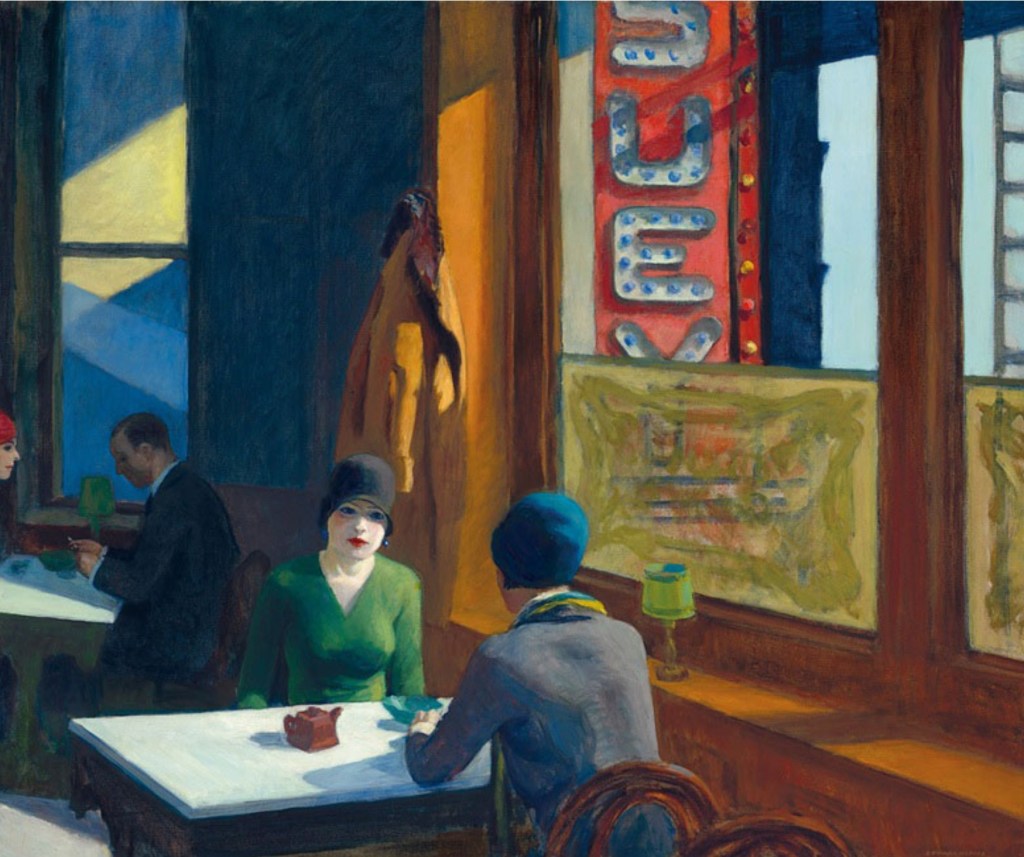

In New York Restaurant, Automat, and Chop Suey, human subjects are portrayed in social situations like an evening at the theater or a restaurant, although none of these pictures tells an actual story. Where the people come from, where they are going, what they are looking at, is peripheral. What primarily interests Hopper is creating a specific atmosphere, transcending the momentary, in which man is viewed comprehensively.

Hopper referred to this intention in a comment on New York Restaurant: “In a specific and concrete sense the idea was to attempt to make visual the crowded glamour of a New York restaurant during the noon hour. I am hoping that ideas less easy to define have, perhaps, crept in also.” It is obvious that his special use of light is important for expressing what is “less easy to define,” namely, the way in which light isolates the human figure in a room, and how light and shadow formations become an independent element, thereby giving the interior new shape and meaning. The viewer’s eye is led to these zones of light, which are independent of the human figures and objects. The dynamics of the human encounter are lost in this kind of light. The figures are engulfed in a strangely dense atmosphere that impedes their movements and forces them to look into themselves, away from the person facing them, away from the outside world in general. New York Restaurant, for example, is a tranquil painting in which time stands still and the everyday scene has been transformed. Chop Suey, the last painting from the nineteen-twenties, clearly shows the direction Hopper’s art was to take. This painting is a formal construction of lines and flat surfaces in which color and especially light-fields take on an optical reality of their own, independent of the concrete objects depicted.

The predominance of formal values corresponds to the speechlessness and motionlessness of the figures. Furthermore, it becomes clear that this play of light imbues the objects with special importance in contrast to the human subjects. The pot and bowl on the table, each a visual unit together with its shadows, are meant to be not objects used by man but primarily a combination of form and color, thereby assuming an independent existence. This autonomy is also evident in the neon sign outside and the coat hanging to the left. Since both of these objects are traversed by a field of light, their status as independent objects is particularly striking. What we observe here is a living exchange between objects and light, taking place without man’s awareness. The objects can, of course, be recognized and classified according to their everyday function, but at the same time they are portrayed as formal, abstract entities and thus take on an independence apart from their usefulness. For an understanding of Hopper’s work, it is essential to recognize the autonomy the objects have assumed.’

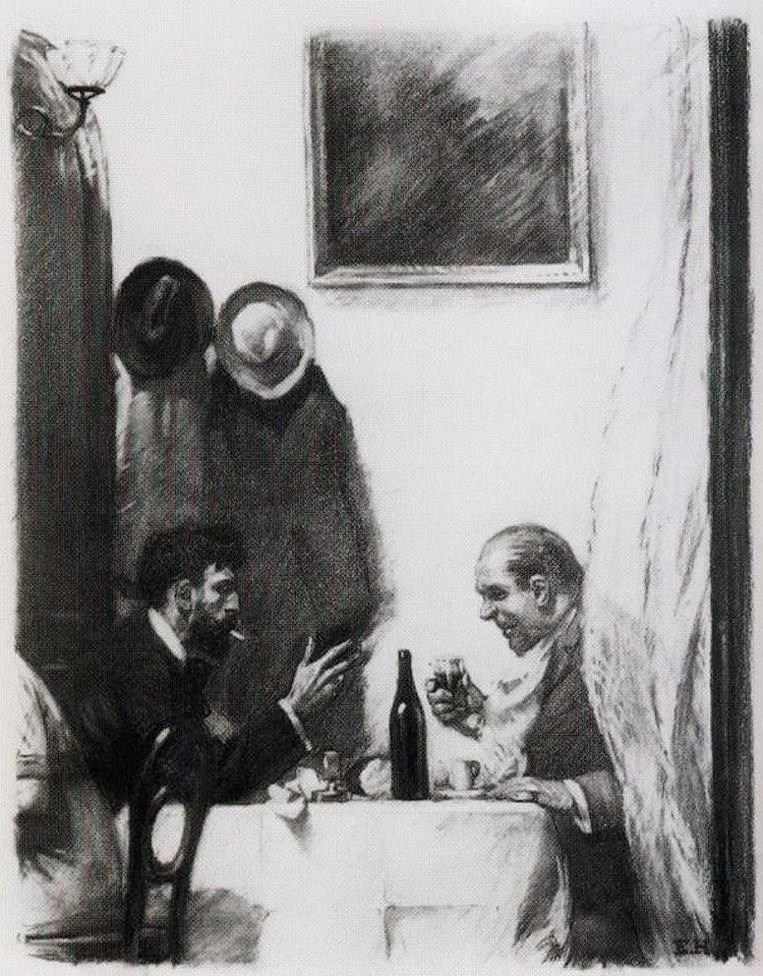

Edward Hopper

In a Restaurant (1916-25)

Etching on off-white wove paper

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Edward Munch, Outdoor Restaurant, 1926. Drawing.

Crayon, multicoloured

Wove paper

Dimensions: 244 × 313 × 0.08 mm.

Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway

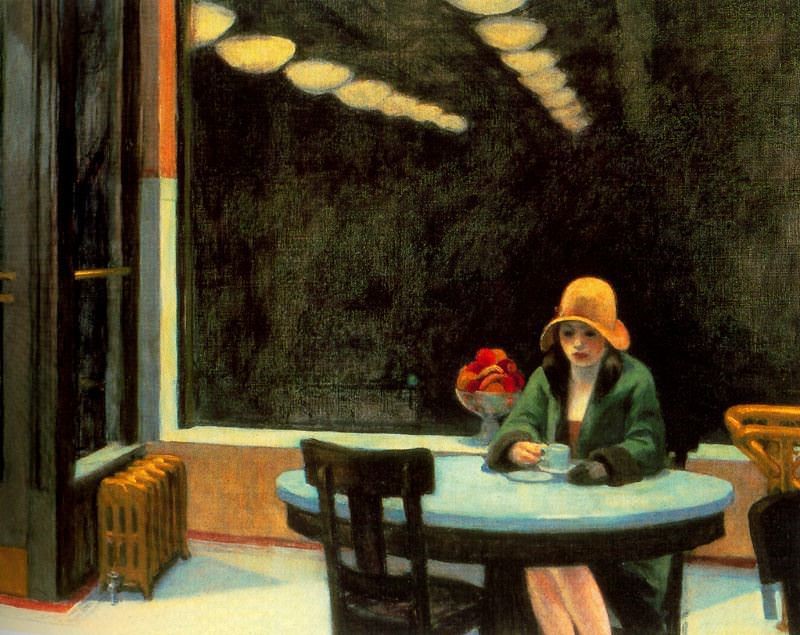

Automat, Edward Hopper, 1927, Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 71.4 cm × 91.4 cm (28 in × 36 in)

Collection: Des Moines Art Center

Automat is a 1927 oil painting by the American realist painter Edward Hopper. The painting was first displayed on Valentine’s Day 1927 at the opening of Hopper’s second solo show, at the Rehn Galleries in New York City. By April it had been sold for $1,200.

A coin-operated glass-and-chrome wonder, Horn & Hardart’s Automats revolutionized the way Americans ate when they opened up in Philadelphia and New York in the early twentieth century. In a country where the industrial revolution had just taken hold, eating at a restaurant with self-serving vending machines rather than waitresses and Art Deco architecture instead of stuffy dining rooms was an unforgettable experience. The Automat served freshly made food for the price of a few coins, and no one made a better cup of coffee. By the peak of its popularity—from the Great Depression to the post-war years—the Automat was more than an inexpensive place to buy a good meal; it was a culinary treasure, a technical marvel, and an emblem of the times.

‘The painting portrays a lone woman staring into a cup of coffee in an Automat at night. The reflection of identical rows of light fixtures stretches out through the night-blackened window.

Hopper’s wife, Jo, served as the model for the woman. However, Hopper altered her face to make her younger (Jo was 44 in 1927). He also altered her figure; Jo was a curvy, full-figured woman, while one critic has described the woman in the painting as “‘boyish’ (that is, flat-chested)”.

As is often the case in Hopper’s paintings, both the woman’s circumstances and her mood are ambiguous. She is well-dressed and is wearing makeup, which could indicate either that she is on her way to or from work at a job where personal appearance is important, or that she is on her way to or from a social occasion.

She has removed only one glove, which may indicate either that she is distracted, that she is in a hurry and can stop only for a moment, or simply that she has just come in from outside, and has not yet warmed up. But the latter possibility seems unlikely, for there is a small empty plate on the table, in front of her cup and saucer, suggesting that she may have eaten a snack and been sitting at this spot for some time.

Hopper would make the crossed legs of a female subject the brightest spot on an otherwise dark canvas in a number of later paintings, including Compartment C, Car (1938) and Hotel Lobby (1943). The female subject of his 1931 painting Barber Shop is also in a pose similar to the woman in Automat, and the viewer’s image of her is similarly bisected by a table. But the placing of the subject in a bright, populated place, at midday, makes the woman less isolated and vulnerable, and hence the viewer’s gaze seems less intrusive.‘

See also: Edward Hopper’s Automat – A Haunting Depiction of Urban Alienation

Lotte Laserstein, Im Gasthaus / In the Tavern, 1927

Laserstein was one of the first women to study art at the Berlin Academy and after Im Gasthaus appeared in the academy’s annual exhibition in 1928 it was purchased by the City of Berlin, a considerable honor for the young artist.

The painting shows a “neue Frau” alone in a bar, her hair bobbed in the new, more masculine style, her deflected expression pensive, intense. Lotte Laserstein, defined as “three-quarters Jewish” under the Nuremberg Laws, fled to Sweden in the Nazi period and stayed there the rest of her life, where she continued to paint.

Edward Hopper, Chop Suey, 1929. Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 32 x 38 in (81.3 x 96.5 cm)

Private collection

The 1929 masterpiece was sold for $91,875,000 (including buyer’s premium) on 13 November 2018.

‘As art historian Robert Hobbs has written, American painter Edward Hopper (1882-1967) was concerned above all ‘with general human values’, using art ‘as a way to frame the forces at work in the modern world’. Chop Suey (1929), the most iconic painting by Hopper left in private hands, epitomises the psychological complexity for which his work is celebrated, freezing in place an everyday scene from an America that was changing rapidly.

In his early years Hopper studied painting at the New York School of Art under Robert Henri, the leader of the Ashcan School, which emphasised a gritty realism. Although his style would transform over time, Hopper never abandoned Henri’s central teaching: to paint the city and street life he knew best. While some of his contemporaries focused on the flamboyant flapper set, Hopper trained his eye on the quieter, quotidian dramas unfolding in unpretentious places such as Chinese restaurants, automats and diners.

Derived from the Cantonese phrase tsap sui, meaning ‘odds and ends’, chop suey restaurants had by the mid-1920s evolved into popular luncheonettes where the new working class could grab a bite to eat. Hopper’s oil paintings were often a result of a combination of his past experiences, and it is thought that Chop Suey was partially inspired by two restaurants the artist visited in the 1920s.

The Far East Tea Garden, located at 8 Columbus Circle on New York City’s Upper West Side, was a second-floor spot that Hopper and his wife Josephine frequented in the early years of their marriage. The Empire Chop Suey in Portland, Maine, where the Hoppers spent the summer of 1927, boasted a similarly striking sign — 24ft high and weighing 600 pounds — to the one that features so prominently in the painting. Neither establishment still exists.

In Chop Suey, two women sit at a table, with another couple partially visible in the background. The bright white tables are conspicuously empty, with only the Asian teapot on the near table suggesting any Chinese influence. Art historian Judith A. Barter has explained that this is characteristic of Hopper’s style: ‘There is never anything to eat on Hopper’s tables. Famously uninterested in food, Hopper and his wife often made dinner from canned ingredients. What he found important were the spaces where eating and drinking took place.’

Hopper’s restaurant paintings reflect the shifting role and view of American women in the late 1920s. Chop suey joints were spaces where the new female workforce was welcome — indeed, the woman facing the viewer is the painting’s focal point. But rather than basking in the light streaming in from the restaurant window, she appears pensive, avoiding eye contact with either the viewer or her companion.

Posed for by Josephine Hopper — as were all three female figures in the scene — she seems removed from the woman sitting just across from her. This sense of distance is heightened by Hopper’s practice of using light almost as a theatre spotlight, contributing an unsettling sense of solitude.

‘In New York’s restaurants, women, especially young ones, were on public display as never before,’ explains Patti Junker, curator of American art at the Seattle Art Museum. ‘Hopper’s restaurant pictures all focus on these young working-class women, and thus they understand something essential about the character of the modern city in which he painted. They reveal, too, the social and sexual tensions that came with new public roles for men and women. Hopper’s New York café women of the 1920s are among his most psychologically and sexually charged character studies.’

Hopper plays as much with colour and light as he does with mood. In the background, swathes of cool blues are bisected by bands of strong white light, casting a near-abstract pattern on the walls. The warm hues in the foreground, meanwhile, draws attention to the striking red, white and blue of the gleaming sign outside.

It was perhaps this play of light and form that so attracted Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko, who was inspired by Chop Suey in his early career. In incorporating the bold signage of the city streets, Chop Suey also foreshadows Pop Art, with Hopper’s exploration of the commoditisation of dining in the 1920s anticipating the themes of Pop Art a half-century later.’

Chop Suey (1929) — the most iconic Edward Hopper painting left in private hands

Eaton’s Restaurant on the 9th floor Montreal

On January 26, 1931, the new Eaton’s Ninth Floor Restaurant in Montréal opened at 11:00 AM, just in time for the first lunch crowd.

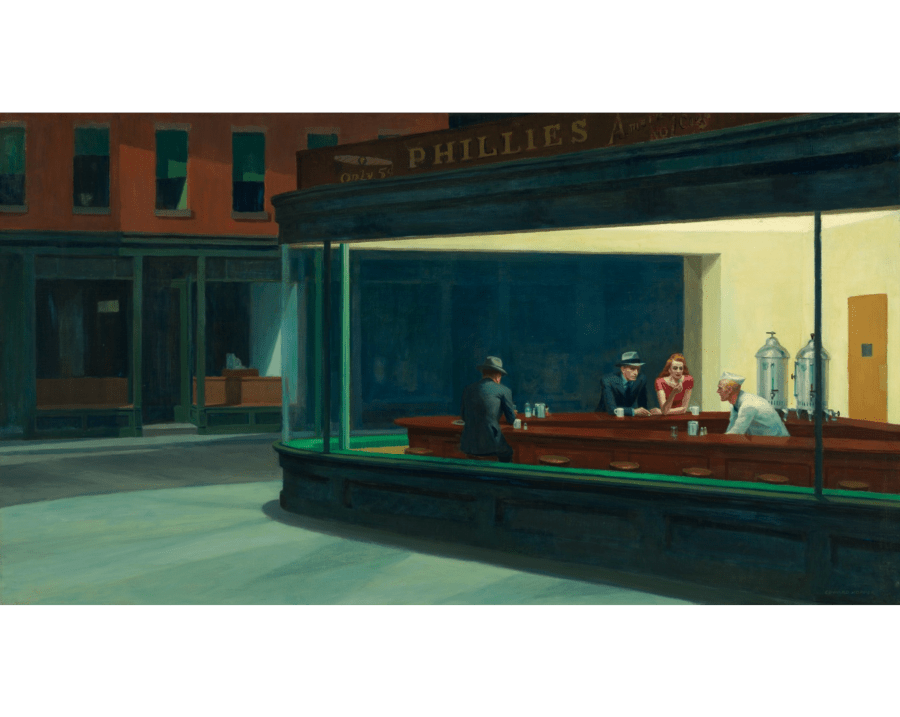

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942, Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 84.1 × 152.4 cm (33 1/8 × 60 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago’s ‘Nighthawks’ page is rich in material. I quote the introductory paragraph.

‘About Nighthawks Edward Hopper recollected, “unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” In an all-night diner, three customers sit at the counter opposite a server, each appear to be lost in thought and disengaged from one another. The composition is tightly organized and spare in details: there is no entrance to the establishment, no debris on the streets. Through harmonious geometric forms and the glow of the diner’s electric lighting, Hopper created a serene, beautiful, yet enigmatic scene. Although inspired by a restaurant Hopper had seen on Greenwich Avenue in New York, the painting is not a realistic transcription of an actual place. As viewers, we are left to wonder about the figures, their relationships, and this imagined world.’

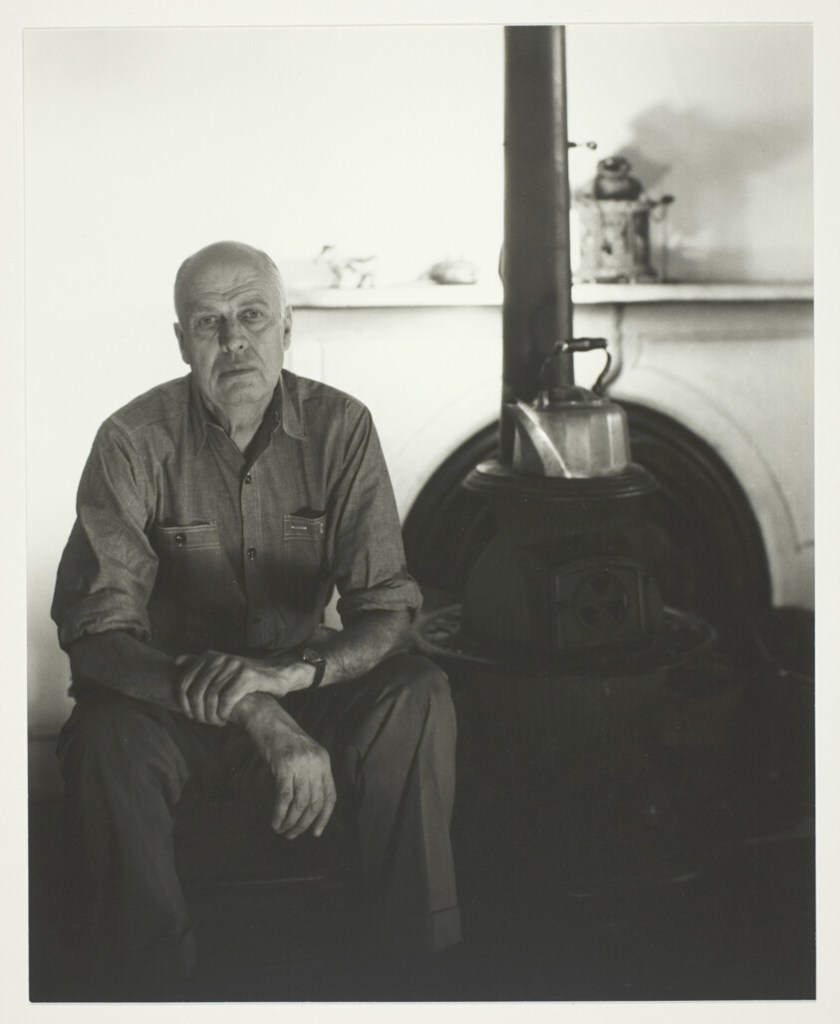

I close the post with a beautiful photo of Edward Hopper.

George Platt Lynes. Edward Hopper, 1950

Gelatin silver print

Dimensions

Image/paper: 24.1 × 19.5 cm (9 1/2 × 7 11/16 in.); Mount: 35.6 × 28 cm (14 1/16 × 11 1/16 in.)

Art Institute of Chicago

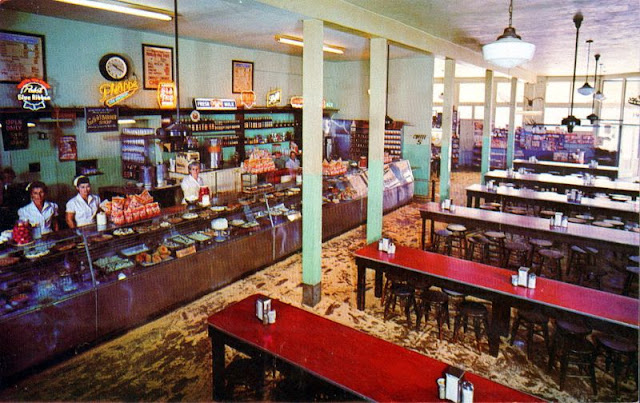

Great French dipped sandwiches and hardboiled eggs.

Philippe’s removed the long tables after the Covid epidemic and made space for a line to queue and have not reinstalled the long tables.

Warren Platner, The American Restaurant, in Kansas City, USA, 1974

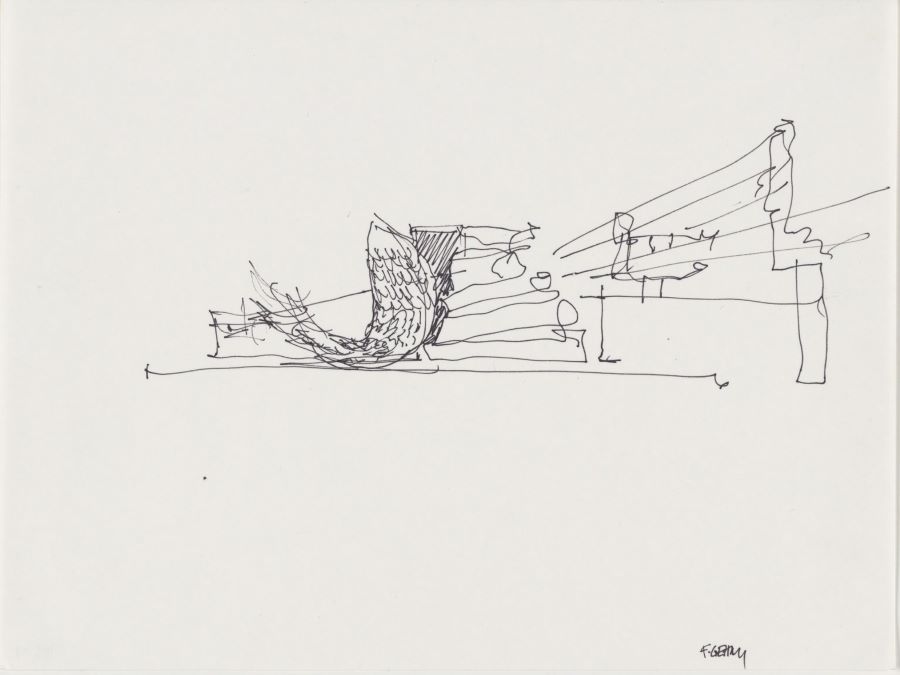

Frank O. Gehry. Sketch for Fishdance Restaurant, Kobe, Japan, Exterior perspective. 1986-87

Caffe La Crepa, Isola Dovarese, Italia

Ristorante Imago, Hassler Hotel, Rome, Italy

The chairs surround a table in the dining room of the Frank Lloyd Wright Suite at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan, Friday, August 19, 2016. Photographer: Tomohiro Ohsumi/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

Tudor Hall Restaurant, King George Hotel, Athens, Greece

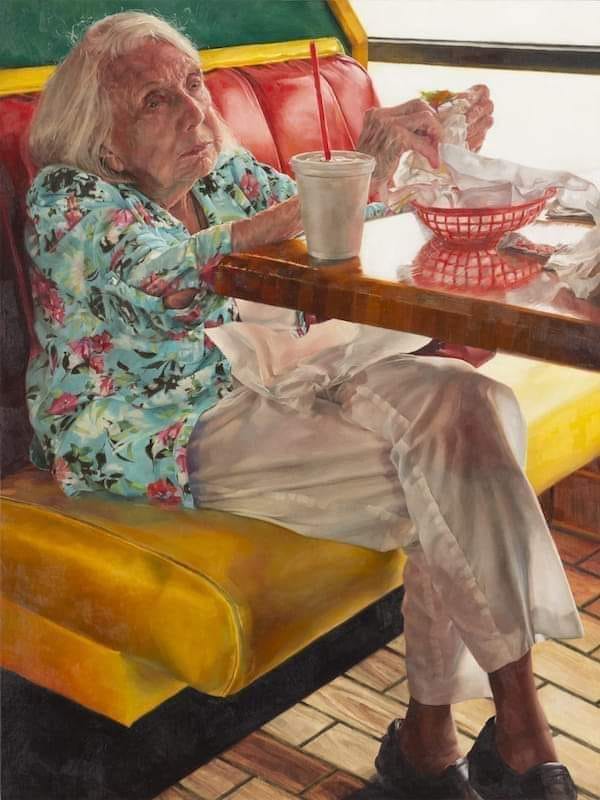

Amy Werntz (American Artist, born 1979)

“Lunch”, 2021.

Oil on Panel, 26 × 20 inches.

The Bennett Collection of Women Realists, San Antonio, Texas, USA.