Updated 26th June 2024.

Starting with a dish from Campania, I present some still life fish paintings by Chardin, Melendez, Manet and Soutine.

Painter of Lyon

Dish with skate, electric ray, perch and red mullet, 350 – 325 BC

Red figure ceramic

Found in Campania, Italy

Hauteur : 4,3 cm ; Diamètre : 16 cm ; Poids : 0,279 kg

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Jean-Siméon Chardin was born in Paris on 1699, the son of a carpenter. Until 1757 he lived on the left bank of the river Seine, near the Church of Saint-Sulpice. That year the King Louis XV offered him a flat in the Louvre. Chardin died in Paris on the 6th December 1779, at the age of 80 years. Following his apprenticeship with the history painter Pierre-Jacques Cazes, Chardin spent time in the studio of Noël-Nicolas Coypel studying 17th-century Dutch and Flemish painting, whose influence is evident in his early still lifes. In 1728 he participated in the Exhibition of Young Artists in the Place Dauphine, showing works that included The Rayfish (Musée du Louvre). Chardin’s work was praised by Largillière and that artist was influential in Chardin’s admission to the Académie that year. Chardin entered as a painter of animals and fruit, presenting his famous Rayfish and The Sideboard (also in the Louvre). The artist again took part in the Exhibition of Young Artists in 1732 and 1734. From the 1730s he began to produce his first compositions with figures depicted at home and engaged in their everyday tasks. These simple but dignified scenes offer a record of the life of one sector of French society. Among them are The Governess (Galerie Nationale du Canada, Ottawa), The Scullery Maid and The Tavern-keeper (both Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow). With the reopening of the Salon in 1737, Chardin regularly exhibited his work there. In 1755 he was unanimously elected as treasurer of the Académie, a position he occupied until 1774. In 1756 he returned to still-life painting. Chardin painted 120 still lifes and often painted the same ‘humble’ objects like cups, teapots, prunes, peaches. He switched the objects around, adding or removing one or more objects, always aiming at achieving a balanced composition. He only used objects that belonged to him, and always painted with the complete composition being in front of him, from the first to the last brush stroke, without a preparatory drawing.

He was a contemporary of Francois Boucher (1703 – 1770) and taught Honore Fragonard (1732–1806), but his style was different, emphasizing the natural aspects of the objects without frills, in contrast to the lightness, playfulness and charm of rococo. In 1770 and as a result of his failing sight, Chardin began to focus on pastel, a technique in which he produced various portraits, among them those of his wife and a Self-portrait. They were exhibited in the Salon in 1775 and are now in the Louvre. Chardin’s work was a reference point for artists such as Manet, Cézanne and Morandi. His paintings revealed the poetry hidden in humble objects. transporting the viewer to a down to earth world that is experienced with directness and simplicity.

Jean Simeon Chardin, The Rayfish, Other title: Kitchen Interior (La Raie, Autre titre: Intérieur de cuisine), 1725-1726, Oil on Canvas

Height : 1,145 m ; Height with frame : 1,455 m ; Length : 1,46 m ; Length with frame : 1,775 m ; Frame depth : 10 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

The Rayfish is one of the most famous Chardin paintings. The naturalism of the subject is superficial. The painting generates dramatic intensity. The fish is cut in many places and hangs from a hook on the wall, its down side facing the viewer, exposing its bludgeoned guts to him/her. The intensity is fuelled by the limited palette used by Chardin. The magnificence of the butchered rayfish beautifies it. The picture’s setting has nothing to do with a functioning kitchen. Half of the knife is in the air, adding depth to the picture. The tablecloth is folded elegantly. Chardin has bene influenced by the still lifes of the 17th century masterpieces, like Rembrandt’s ‘Slaughtered Ox’ (1655).

Jean Simeon Chardin, Still-Life With Cat and Rayfish, 1728

Oil on canvas. 79.5 x 63 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Chardin is represented in the Museum’s collection by three outstanding still lifes: the present pair, dating from 1728, and a still life with a pestle and mortar, pitcher and small copper cauldron or cooking pot, dating to some years later. The naturalist trend to which Chardin’s art can be ascribed co-existed in 18th-century France with the Rococo style. Objects are the protagonists of his paintings, which vary and change their role according to the composition and in relation to each other. It has been said that Chardin was the painter of the middle-classes, whom the artist represented in scenes with figures in the 1730s, in which these figures are surrounded by everyday objects that form part of their environment. Chardin’s still lifes are arranged with objects that belonged to him and which he repeatedly used in his compositions. Very few preparatory drawings are known, a fact that tallies with his unusual working methods. According to Mariette in his Abecedario, Chardin needed to have the model continually within sight from the first brushstrokes to the final touch. The same author also noted that Chardin sold his paintings for higher prices than other painters working in traditionally more prestigious genres such as figure painting.

The present pair of canvases, which was in the collection of Baron Edmond de Rothschild, was acquired for the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection in 1986. The oldest known references to these canvases locates them in the collection of Rémond, ancien maître d’hôtel du roi, after which they were auctioned in 1778. They seem to have belonged to Armand-Frederic Nogaret and were auctioned in Paris in 1807. In the 19th century they were to be found in the collection of the Baron de Beunonville and were auctioned in 1881 and 1883. In the 20th century they belonged to Leon Michel-Levy then Baron Maurice and Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

Both oils reflect the influence of Dutch painting that is evident in the artist’s early work, in which he adapted northern subjects and formats to his own manner. Still Life with Cat and Fish is signed and dated 1728, a date that was incorrectly read as 1758 in the literature prior to 1979 as it is difficult to decipher. On the occasion of the monographic exhibition on the artist held that year, Rosenberg and Caritt corrected the date to 1728, which is more appropriate to the style of the two canvases. On 25 September of that year Chardin was admitted to the Académie as a painter of fruit and animals.

That period, during which he painted two of his masterpieces (The Rayfish of around 1725 and The Sideboard of 1728) and which is most clearly influenced by Dutch art, Chardin began to accompany his silent, motionless objects with living animals that interrupt the tranquillity of the scene. These two canvases with their simple compositions of a stone ledge on which the cats, foodstuffs and kitchen vessels are arranged, break their horizontal emphasis through fish hanging from hooks above them. The rich colouring, applied with a thickly charged brush and delicate touches of paint across the surface, creates a realistic, visually convincing representation. The chromatic range used in the fish scales and the cats’ fur would be admired by painters of the following generation such as Descamps. The spirit of these two works is different to that found in his famous Sideboard in which he replaces the cat with a dog and depicts a table with objects and exquisite foodstuffs. There are two versions with variants of the present pair in the Nelson-Atkins Museum and the Burrell Collection in Glasgow.

Max Borobia

Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin, Still Life With Cat and Fish, 1728

Oil on canvas. 79.5 x 63 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Meléndez, Luis Egidio, Still Life with Salmon, Lemon and three Vessels, 1772, Oil on canvas.

Height: 41 cm; Width: 62.2 cm

Museo del Prado

This superb example of the artist’s virtuosity at capturing elements with a direct and realistic language can be considered a work from late in his career. A sole lemon in the foreground offsets the group of elements consisting of a slice of fresh salmon and various cooking utensils, including a copper vessel, a pot of the same material and an Alcorcón style jug with a bit of crockery as a lid. A handle in the background might belong to a ladle. The surface on which these items sit disappears into the background. Its edge is emphasized by a spoon with a very long handle.

Meléndez, Luis Egidio, Still Life with Breams, Oranges, Garlic, Seasoning and Kitchen Utensils, 1772, Oil on canvas

Height: 42 cm; Width: 62.2 cm

Two splendid sea breams play the leading role here. They are surrounded by lesser motifs, including oranges, a kitchen towel, a head of garlic, and packet of what is probably spice, two terracotta bowls from Alcorcón, a long-handled pan, a mortar whose pestle leans into the background, and a cruet that participates in this work’s careful study of light as a means of defining volumes, diversifying the shades of color and distinguishing the qualities of the different materials. The result is a pictorial spectacle filled with details that reflect a powerful realism imbued with the poetic nature of the everyday.

Here, the artist reveals his tendency to work with pure geometric forms and his fondness for capturing the intimate traces of each object, endowing them with perfect spatial dimensions. In that sense, we detect a peculiar underlying play of compensated cones and truncated cones that very successfully complete the group in the background. Overall, the structural impulse is astonishingly confident, bringing a vital dynamism to the composition from the cruet to the fish, which rises as a sort of singular central monolith and reference point for the vertical elements that correspond to its linearity. Together, these two stimuli generate a cohesively balanced grid perfectly adapted to the silent serenity that this work offers the viewer.

The present work contributed to Meléndez’s reputation as an outstanding still-life painter as its combination of extraordinarily successful elements stands head and shoulders above many other works in this series made for Charles of Bourbon, prince of Asturias, who would later rule as Charles IV (1788-1808). Painted under the reign of Charles III (1759-1788), it strongly reflects the desire to show the type of foodstuffs produced in the vast terrain of the Spanish Empire, as the painter himself stated in one of his texts.

Either this work was successful, or the artist himself considered it particularly special, as there are numerous almost-identical replicas in different collections. Of course, this is hardly surprising in such a splendid rendering of the artist’s refined vision of the day-to-day world in a kitchen of his time. Today, it continues to astonish those who appreciate it for its esthetic and technical achievement.

Luna, Juan J., El bodegón español en el Prado: de Van der Hamen a Goya, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, 2008, p.118/119

Eugene Boudin, Ray and Vase, Watercolor and graphite

H. 0,074 m ; L. 0,119 m

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Édouard Manet, Fish (Still Life), 1864, Oil on canvas

Dimensions

73.5 × 92.4 cm (28 15/16 × 36 3/8 in.)

Although still-life ensembles were an important element in many of the major paintings of the avant-garde artist Édouard Manet, his most sustained interest in the genre itself was from 1864 to 1865, when Fish was painted. Manet’s focus on still lifes coincided with the gradual reacceptance of the genre during the nineteenth century, due in part to the growth of the middle class, whose tastes ran to intimate, moderately priced works. This painting, like many of Manet’s still-life compositions, recalls seventeenth-century Dutch models. The directness of execution, bold brushwork, and immediacy of vision displayed in the canvas, however, suggest why the public found Manet’s work so unorthodox and confrontational. While Fish is indeed an image of “dead nature” (nature morte is the French term for still life), there is nothing still about the work: the produce seems fresh and the handling of paint vigorous. Further enliven-ing the composition is the placement of the carp, which offsets the strong diagonal of the other elements. Manet never submitted his still lifes to the official French Salon but rather sold them through the burgeoning network of art galleries in Paris and gave them to friends.

Édouard Manet, Still Life with Fish and Shrimp, 1864, Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 17-5/8 x 28-3/4 in. (44.8 x 73 cm)

Credit Line: Norton Simon Art Foundation

Norton Simon Museum

As the critic Émile Zola explained in 1866, “Even the most determined enemies of Édouard Manet’s talent admit that he paints inanimate objects well.” Unlike the ambitious figure paintings he sent to the Salon year after year, Manet’s modest still lifes were universally admired in his own time. Stripping the genre of its allegorical associations—fasts and feasts, time, the seasons, the senses—compositions like this one excused early viewers from the need to decipher a story or conventional meaning, freeing them instead to admire Manet’s deft, succinct application of paint, evident in the salmon’s glittering, impasted scales, the long, elegant strokes of the needlefish’s head, and the dainty, filigreed shrimp.

Édouard Vuillard – “Le Hareng saur”, 1888

Winslow Homer, Life-Size Black Bass, 1904

Medium: Transparent watercolor, with touches of opaque watercolor, rewetting, blotting and scraping, over graphite, on thick, moderately textured (twill texture on verso), ivory wove paper (left, right and lower edges trimmed)

Dimensions: 35 × 52.6 cm (13 13/16 × 20 3/4 in.)

In January 1904, Homer traveled to Homosassa, Florida, to fish. The Homosassa River, on the gulf side of the state, was home to many fish species and supported a lush wildlife habitat. It was in Homosassa that Homer painted his final tropical watercolors, including Life-Size Black Bass. In this work, the artist placed the underside of the huge, brightly colored fish at center and close to the viewer, bringing alive the drama, immediacy, and excitement of the fisherman’s experience as his fly, a “scarlet ibis,” hangs in the air. With trademark ambiguity, Homer presented the bass suspended between life and death. Will it succeed in grabbing its bright target only to seal its fate? The fish’s sudden jump slices through the dark, quiet jungle with a momentary flash of life and color.

In order to force the viewer into the path of the leaping fish, Homer cropped three centimeters off the lower edge of Life-Size Black Bass. He then centered and framed the fish for maximum effect by trimming a total of 2 centimeters from the right and left edges. The sheet dimensions are 350 x 526 millimeters; the original sheet dimensions were 380 x 545 millimeters as compared with uncut sheets of the same paper type. The trimmed edges appear slightly uneven and lack any adhesive residue from the watercolor paper block. As in a photograph with a short focal length, Homer presented the fish in tight focus against a vague and fluid background. With these compositional choices Homers heightened the tension of the strong, vital bass, frozen in motion, before capture and death. Such dramatic psychological impact results from Homer’s three decades of persistent observation using watercolor to transcribe nature on paper.

Still Life with Fish, Chaim Soutine, ca. 1920, Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 16 1/4 × 25 1/4 in. (41.3 × 64.1 cm)

Credit Line: Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), 1967

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Below I quote from the museum’s website.

‘Upon his arrival in Paris in 1913, Soutine worked alongside Modigliani and Chagall in a cluster of artists’ studios called La Ruche, or “The Beehive.” In this early still life, the open mouths of the herrings create the illusion that the fish are gasping for air, prefiguring the dramatic intensity of the artist’s later work. At La Ruche, Soutine also experimented with expressionistic brushwork, as seen in the thick, forceful application of paint.’

The intensity of the herring’s expression preannounces W. G. Sebald’s ecological anxiety as expressed in ‘The Rings of Saturn’.

The picture is in the public domain

Chaïm Soutine, Still Life with Rayfish, 1923, Oil on canvas

Unframed: 80.5 x 64.5 cm (31 11/16 x 25 3/8 in.)

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Inspired by J. S. Chardin’s 1725–26 still life of a stingray at the Musée du Louvre, Chaim Soutine reinterpreted the theme in a turbulent, luminescent manner. Every line and form undulates as if propelled by some unseen force. Tied up on two points, as if being tortured or crucified, the stingray assumes an expression of almost human anguish, transforming it into a powerful metaphor for suffering, perhaps referring to Soutine’s own life as a poor Jewish artist who emigrated from Belarus to Paris in 1913.

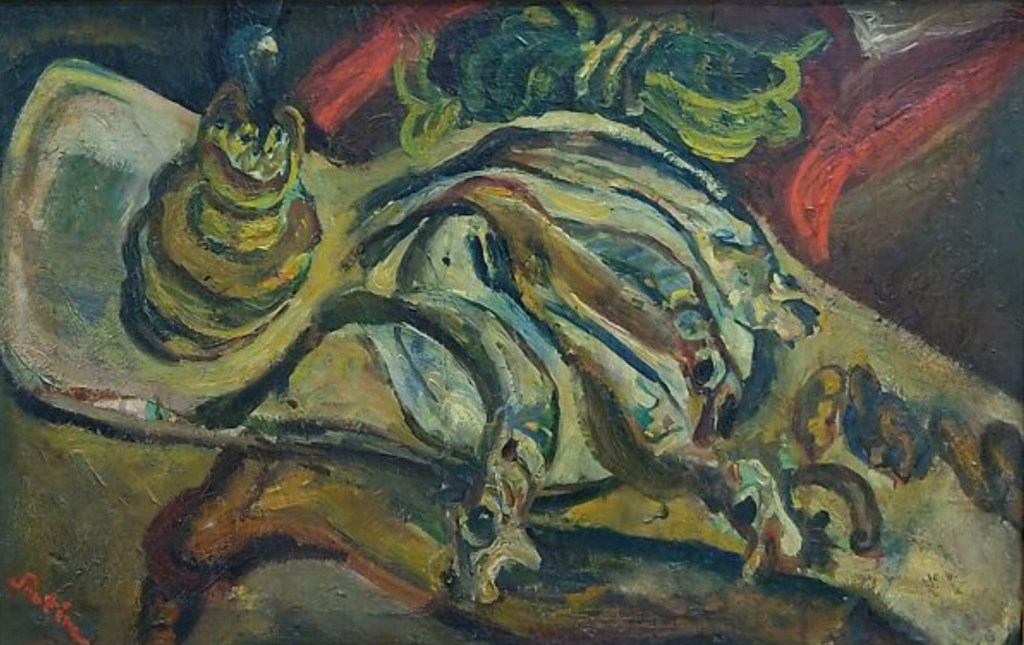

Still Life with Rayfish, Chaim Soutine, ca. 1924, Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 32 × 39 3/8 in. (81.3 × 100 cm)

Credit Line: The Mr. and Mrs. Klaus G. Perls Collection, 1997

Rights and Reproduction: © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In this unsettling adaptation of Jean-Siméon Chardin’s The Rayfish (ca. 1725–26), Soutine paired the fish’s bloody entrails with a smiling, almost humanlike mouth. He reanimated the dead ray by concentrating on its vibrant underbelly and used thick, fluid brushstrokes to suggest slick flesh.

Suzanne Valadon

Nature morte au hareng, 1936